Pablo, Come to Florida…

Looking back on it, Radiohead’s debut album Pablo Honey didn’t have the same initial impact on me that Creep did. But albums take more time to get rooted into your system than single songs. Particularly a song with the immediacy of Creep.

I went into town after school to buy a tape of the album the day it came out. It was to remain a regular fixture in my aging Walkman for the next couple of years. It came without a lyric sheet, so throughout the early spring of 1993, I could be found huddled in the corner of the 6th form Common Room with a rosehip tea, (no milk, no fridge and no proper tea), trying to conceal my contraband headphones. I’d shuttle the tape back and forth, stopping and starting my way through a song, trying to fathom the harder to hear lyrics. I would then scrawl them on the outside of my ring binder or on spare note book pages. I’d listen to the songs all over again with new ears, finding things to identify with between A-Level classes, filling in time and filling in the UCA and PCAS university application forms.

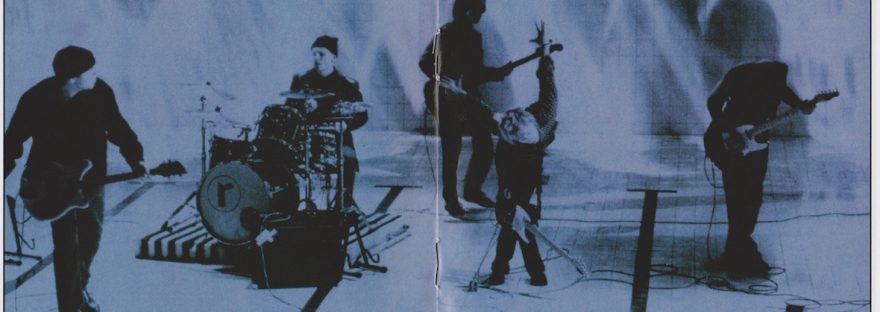

Even after just one live show, it was obvious that Pablo Honey was only an attempt to capture what Radiohead really sounded like. On stage they had a power that they were yet to capture on record. The volume and energy in a song like Blow Out was only approximated on the album. On early listens my favourites were Vegetable and Ripcord. I came to love Thinking About You and Anyone Can Play Guitar, but Stop Whispering and You never really came close to their angry, yearning live incarnations.

Without sufficient musical knowledge of the band’s influences or even much experience of their immediate contemporaries. I couldn’t really judge the record on anything but a visceral level.

To me, it was the best thing going and I was blind to its weaknesses.

POP RIP.

I have to pause at this juncture and address a taboo. Bear with me, I’m going to defend Pop Is Dead…

It’s a good thing that YouTube doesn’t let me embed the Pop Is Dead Video. If you’ve seen it before, you won’t want to watch it again.

The thing that people didn’t seem to understand about Pop Is Dead, Radiohead’s much derided 4th single release of 1993, is that it’s actually a complicated and detailed parody. It has to be, right?

Listening to it again now, long neglected, missed off compilations and all but erased from the band’s history, it sounds… well, yes, it does sound quite bad. But I still have a soft spot for it. I can’t help but find it endearing. It was a statement that meant a lot at the time.

In 1993, British music was in the doldrums, the charts were a mess, the influential weekly music press thought Suede were the best thing since sliced bread and national radio was becoming a joke. The listening public had escaped from the clutches of production line pop stars from Stock, Aitken and Waterman’s stable, only to have Take That reach the peak of their first incarnation as favourites of the Saturday Morning TV demographic. In February, Whitney Houston’s I Will Always Love You had been number one since the previous November – a tortuous reign that continued well into Radiohead’s first UK headline tour, when they started performing Pop Is Dead and dedicating it to her. Worse was to come as the likes of 2 Unlimited and Meat Loaf dominated the charts, and thereby also clogged up mainstream radio playlists.

BBC Radio One had not yet gone through the revolution that was to follow the appointment of controller Matthew Bannister and it what still enduring what has come to be known as its “Smashie and Nicey” years. Harry Enfield’s parody of the over the hill DJs was too close for comfort and had become shorthand for an out dated and out of touch institution.

Record companies had for the most part cashed in on the CD boom of the late 1980s and thrived on sales of reissued albums from their back catalogues. As a new signing to EMI, certain members of Radiohead had been known to comment in interviews about how this endless repackaging of artists like Pink Floyd and The Beatles was often at the expense of newer, less established acts. Instead of nurturing new talent, major labels were already starting to sign “Development Deals” which relied on a new band recording a hit album and touring until it made a significant profit, re-paid their advance and made an impact on the balance sheets. It also often involved the band signing over the rights to their work. If the band failed to turn a profit early on, they would risk being dropped before they had chance to record a second, let alone a third album.

Radiohead, who had signed a 6 album deal with EMI, were now in a position to see the machinations of the music industry from within, and it scared them.

Pop Is Dead, much like its predecessor Anyone Can Play Guitar, can be seen as partly about its creator’s ambivalence to the position in which he now finds himself.

As a manifesto, a statement of intent, Pop Is Dead was a bold move. As a potential hit single it was wrong footed in the extreme. The label didn’t get behind it, much to Thom’s dissatisfaction (reports from the May tour around the time of its release describe his dejection about its poor chart performance) and the critics pretty much failed to get the point.

In interviews with the band (which at this point, means interviews with Thom) from the first half of 1993, you get a sense of a man with a vision of how things have to change, but who is not quite yet entirely sure how to change them.

Pop Is Dead was a product of its moment. It was a nasty and loud jolt in the band’s live set. It is a rock-out cacophony and has a piano part in the middle which for better or worse betrays the influence of middle period Queen on the band’s sound. It was supposed to be a rallying cry and it worked on me.

It also confirmed that Radiohead have a wicked and often misunderstood sense of humour.

Very Spinal Tap

March 24, 1993. I got home from school to find a white hand addressed envelope with an Oxford postmark on the mantelpiece. I don’t know anyone in Oxford. This isn’t from one of my regular pen pals and I’m not expecting any correspondence…

I open the envelope and take out three sheets of plain white note paper covered in blue inked scrawl. “Dear Lucy, Please come and see us on our next tour in May. Cos we’re really good live. Yes we are. Maybe.”

The return address, squashed into the top right hand corner: The Official Radiohead –and the PO Box address from the EMI adverts.

This is a letter in reply to the missive I fired off demanding “more information” and that is precisely what it contains. It tells me about writing Pop Is Dead, about how “extremely un rock and roll” the band are, and even details the university degrees of the band members. They are working on material for their next album which is almost finished “apart from the orchestral arrangements and the brass bands. Only joking. Or am I?”

It goes on to tell me that they’re planning to go to Israel where “Creep is bigger than Whitney Houston”.

The letter concludes that this is “all very Spinal Tap” and again implores me to come and see them live “because we are very nice”.

It is signed “love Thom”.

The actual Thom, not some fan club or record company flunky. A personal invitation. I have to see this band again. I sit down and re-read it a couple of times, taking it all in.

I’ve also got a fanzine in the post today, something I sent off for from in the classified adverts at the back of NME. It’s called Catharsis and has interviews with Kingmaker, The Wedding Present, Strangelove and, the reason I ordered it, Radiohead.

It has been neatly typed and photocopied, assembled by hand with photos cut from the pages of the regular press. In it Thom proclaims that he’d “like to change the face of British radio.” That the “British record industry sucks” and that they’re “shooting themselves in the foot because they don’t support new talent”.

He reiterates the points he’s made in the letter about why he’s written Pop Is Dead. “Commercial success never comes from sounding like somebody else. And the music industry’s just forgotten that as far as I can see.” Thom complains.

“Radiohead,” concludes the writer, “are Spinal Tap.”

The article in Select (Headline: Super Creep, by Andrew Collins) was the first bit of press that I saw outside of the weekly NME and MM about the band. It was also one of the first times I saw something similar to what my opinion of them at the time was in print. A lot of their early reviews fixated on their being signed to a major label (when in the eyes of the inkie hacks it was all about indie credibility) or on the photographers uncanny ability to capture Thom pulling a face during a live show.

Radiohead were too middle class, too polite or too mouthy, not sexy enough, not stylish enough, too original or not original enough, often all of these things at the same time. They had too many contradictions – a band from the Thames Valley who didn’t make shoegaze records, a band signed to a big label who released a single proclaiming Pop Is Dead. They seemed very British and yet their album was produced by luminaries of the Boston scene and mixed in the USA to sound more grungy. The press weren’t really sure where to pigeonhole them.