I’m standing outside the Prague Vystaviste with a hot dog in my hand. As I cross the car park in front of the deserted art nouveau industrial palace, I receive a text message: ppl stood up – open soon – hurry!

I speed walk through the first set of gates, past a line of empty flag poles and a block of pavilions, there are several restaurants but all the doors are locked. There’s a weird sign that says something about a “Sausagefest”, the hotdog is gone but I hardly tasted it.

Behind the glass palace are fountains, which my guide book claims are spectacular, but today they are switched off. This place is part deserted fairground and part soulless convention centre. Like Blackpool, like Birmingham, but today the sun is shining.

I recce’d the site a couple of days ago when I first arrived in Prague. My hotel, carefully chosen to be nearest the venue, is a short walk away. While I’ve been here, the stage rig has been rising from a pile of scaffolding on a dried out lawn. A Heras fence around the perimeter now prevents access without a concert ticket.

My phone beeps another text: Everyone’s standing up.

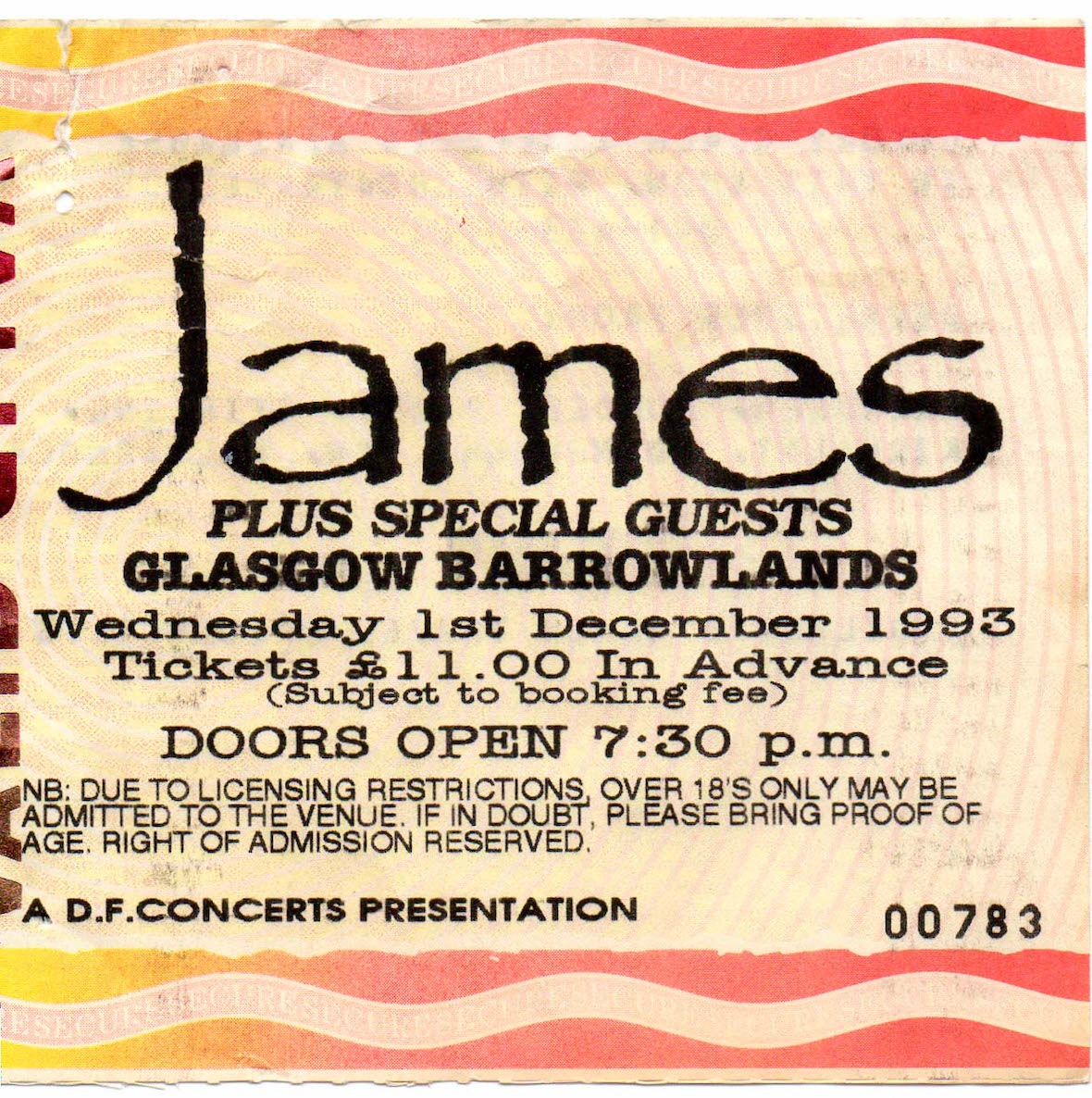

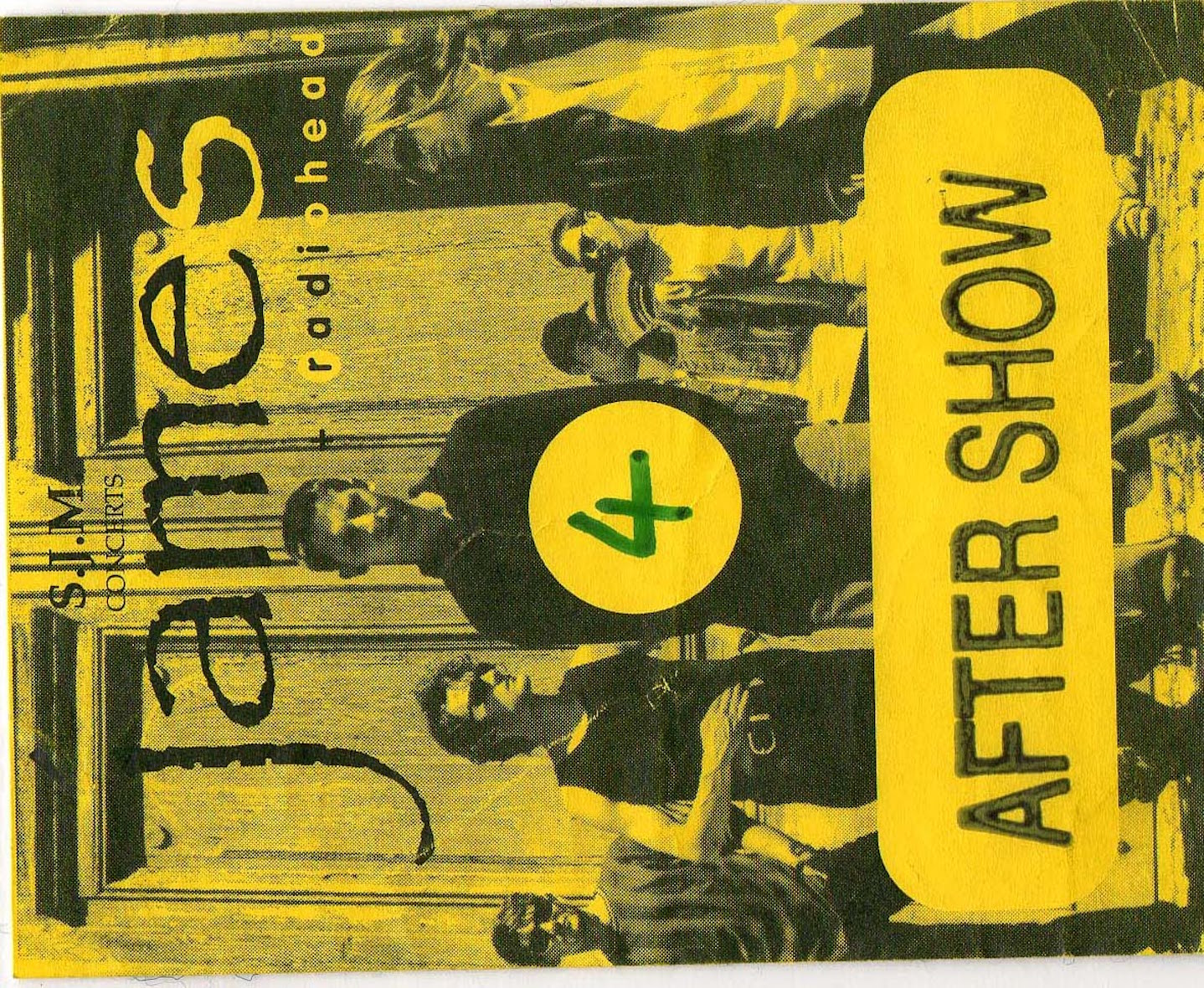

Trying not to run, I follow the path down the park side of the complex. Just before I reach the turnstiles, I stop at a small portacabin where a young crop-haired woman with a laminated pass around her neck presides over the guest list. I have a ticket bought months ago, but as this is a special occasion I’ve asked my contacts for an after show pass. I say my name to the woman and she asks who’s list it is on. The band’s, I say, smiling. For once feeling confident that it will be there. For once not having to spell out my name before it’s found on the print out. She hands me a small white envelope with the words “Aftershow x 2” written underneath my name. I lift the gummed flap, peeking inside as I walk away from the booth. A rush of satisfaction as I bury two triangular fabric stickers marked with today’s date deep in my bag.

The crowd looks denser than it did when I was here an hour ago. Then they’d been sitting on the ground on bits of card or picnic mats, or just on their coats and jumpers; now they’re all standing up facing the turnstiles, like runners poised at the starting gates of some weird horse race. This ritual started hours ago, some of these people have been here since the early hours. They have done this many times before and they know what to expect but it doesn’t lessen the tension. Part of me hates queuing, but today I know that it’s the only way to assure even the possibility of the experience I crave. Today my “support staff ” are here, friends who know what to do to get me through. They know the drill, they are prepared for the fact that I’m not going to be calm.

I’ve done this before, I know that you don’t really need to pitch up in the early hours of the morning. Some fans arrive very early, almost as a point of pride, but you can still get a pretty good spot if you start at a sensible hour. Over the years I have developed my own system, I make a deal with some of my co-queuers: I won’t start ridiculously early but I will bring supplies and guard their spots on the ground while they go for drinks or bathroom breaks. I don’t have the patience to sit for hours getting cold and anxious, so I step in as a relief queuer, rewarded with my own place. I understand some fans’ compulsion to start queuing before it gets light; maybe they feel they are earning the show by making this sacrifice. It’s a way of showing their loyalty, their love.

I reach the back of the huddle and try to find my friends who are somewhere near the front. I shout a couple of names, but they can’t hear me. I stand on tip toes. I try ringing someone’s phone but before they pick up they see me and a hand extends towards me through the throng. I take a deep breath, head down, dive in. Apologising as politely and as Englishly as I can, talking to my friends the whole time, so that everyone else can see that I’m not pushing in, rather returning to the spot I had previously occupied for several hours.

As I forge my way through the crush, I feel a swell in the already palpable excitement. Security operatives take their places at each of the half dozen turnstiles and test the barcode readers that will scan our tickets. There was a rumour that the doors would open at four o’clock. It’s almost 4 now. The atmosphere changes, people stop talking and start concentrating on the gates. Once they are open there will be no time to think. This is the moment to focus. Until now people have waited patiently, but the stress is starting to show. The lucky ones have traveled from across the world to be here. They are experienced and driven individuals, their whole day is geared to reaching their goal. The earliest of them arrived outside the venue at 4am, they waited as the weather got warmer, they held fast as fences and signs were erected around them, they dodged trucks and cherry pickers. They arrived before the venue staff, before the turnstiles were put in place and long before the tour buses even parked. We all have our own well-honed tactics for survival. We distain meals and refuse excessive liquids as these would necessitate strategic planning in order to visit the Portaloos.

I unzip my shoulder bag and tie my jumper around my waist to facilitate a quick search at the gate. People are dumping bags of picnic food, obeying some of the instructions on the detailed signs illustrating what will and will not be allowed inside. Powerful cameras are secreted in clothing, bottles and cans are being emptied or placed on the ground. It feels like someone should blow a whistle to signal the off. The security staff move as a single high-viz unit and release the turnstiles. The crowd ripples and pulls into separate lines behind each gate. Tickets are gripped in sweaty hands as we filter through one at a time, still in orderly fashion but primed to sprint as soon as we need to. I hold my bag open to be examined. The scanner beeps the barcode on my ticket and I’m through.

My friends are in front of me, already round the corner at the next gate where tickets must be shown again and wristbands applied to allow access to the magical ‘Zone 1’. I catch up with my companions and someone grabs my arm. A security guy studies my ticket as his colleague wraps a paper band around my wrist. I’m standing still for this operation, but an over eager young fellow who doesn’t want to wait his turn pushes me. Clarabelle stares him down and pulls me by the hand through to the other side of the traps.

Inside Zone 1 everyone is running the 100 metres to the barrier rail. There is already a line of people there, but it’s only one or two deep. I catch up with my friends again, they’re right in the middle, just behind a trio of fans who make it their mission to stand at the very front for every show having earned that right through traveling long distances and turning up several hours earlier than anyone else.

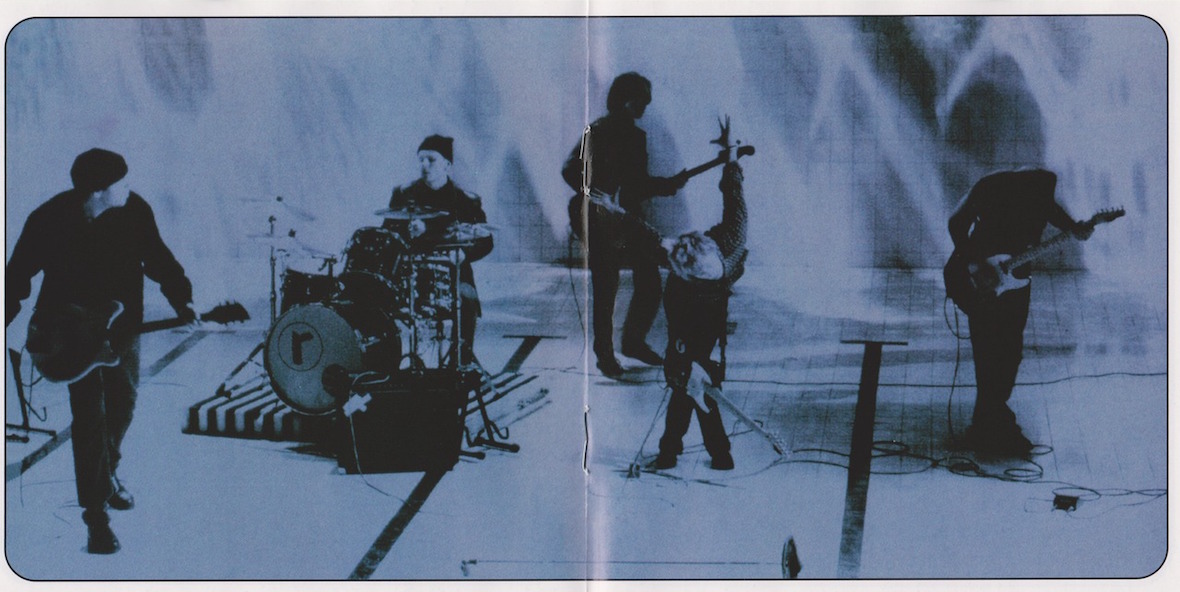

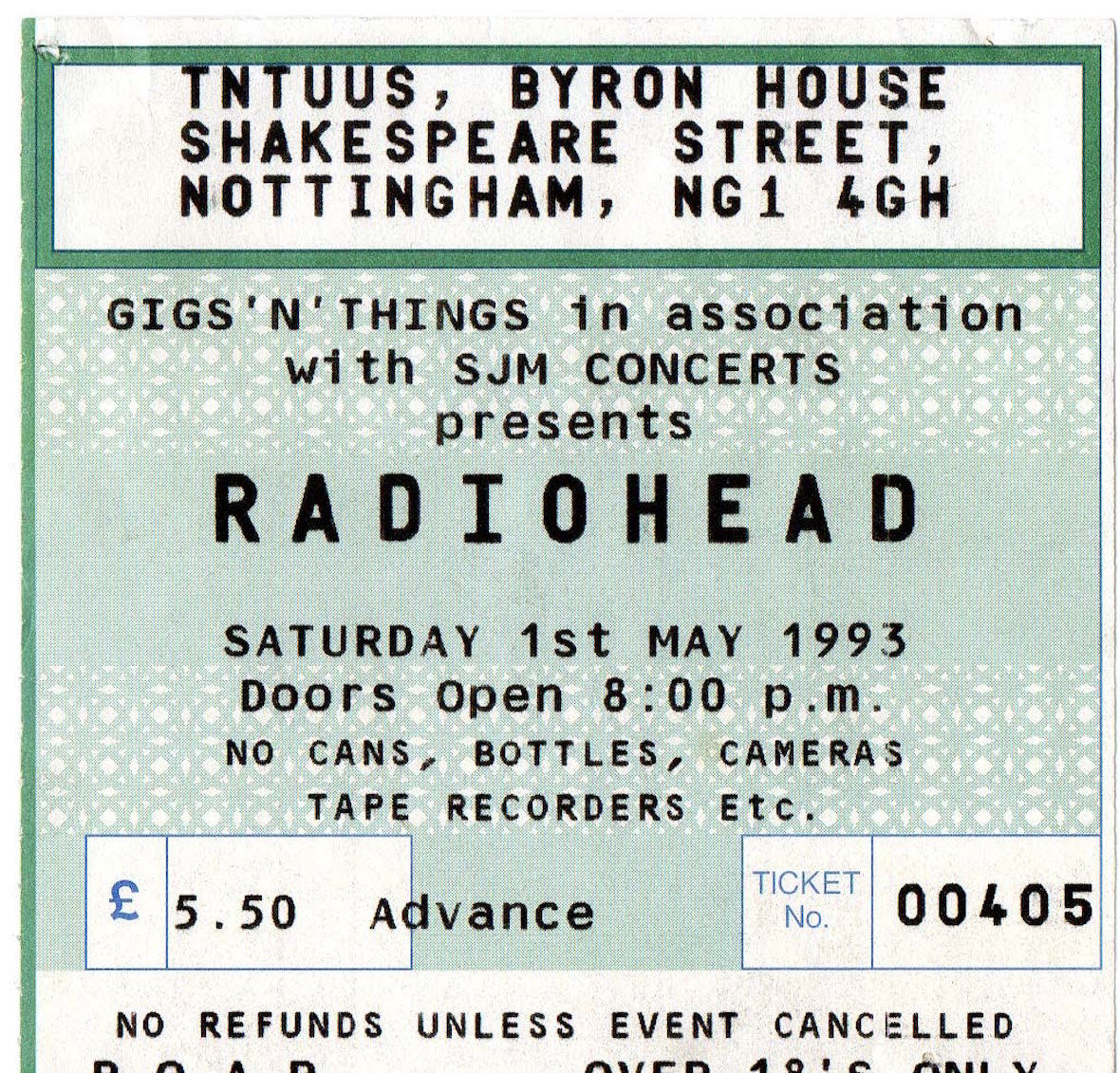

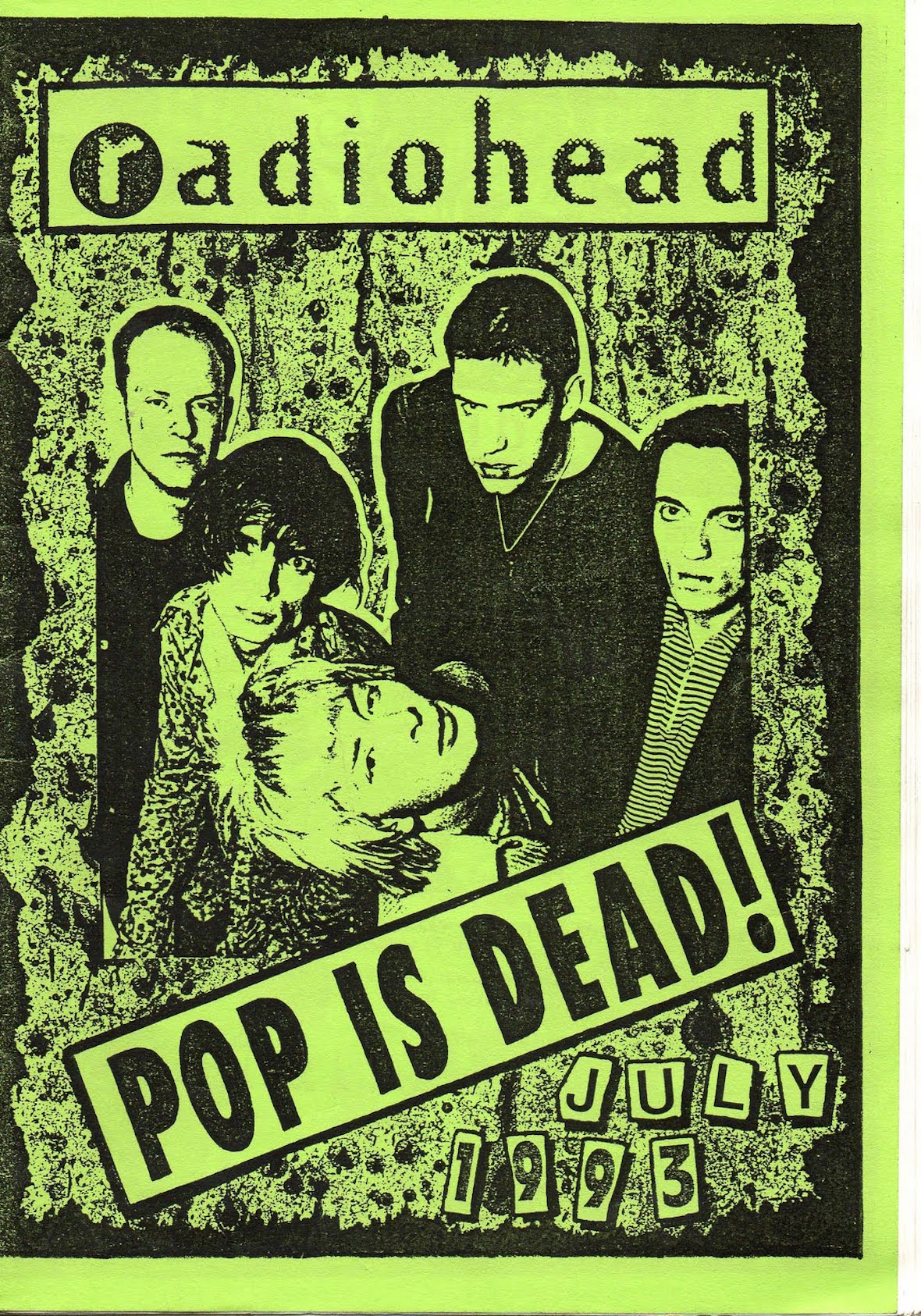

Breathless, excited and relieved, I find I’m in the second row in front of the stage. This will be the 100th time I’ve seen my favourite band, I’ve been doing this for nearly half my lifetime but it hasn’t got any less exhilarating.

People continue to arrive all around me, they run in from the entrance turnstiles, we watch them have their tickets scanned, their bags searched, watch them become irritable with the perceived slowness of the stewards. They push and shove a little but are on the whole polite and respectful of the queuing hierarchy. With a few places at the front still left open, there are displays of sprinting that would not be undertaken under any other circumstances. They swoop in like birds joining a roosting colony and hug each other when they land.

Carefully selected tunes test the sound system. Curtis Mayfield’s Move On Up, some James Brown, some dub. I’m bursting to work out my pent up frustration, dying to dance but I know I should conserve my energy, so I sit down on the ground and stake out my territory.

I am greeted by old friends and acquaintances, some of whom I only ever see at these gigs, some of them are people whose sofas I have slept on, some of them are people who until now have only existed as a name on the internet. This part of the day has become almost as important to us as the performance. I’m jumpy and anxious, but I’m part of this strange community now and they understand what I’m feeling.

We have reached The Barrier. We will have an unfettered view, we will take the best photos and we will hang on for dear life. We will be the most completely immersed in this performance. We are all grinning.

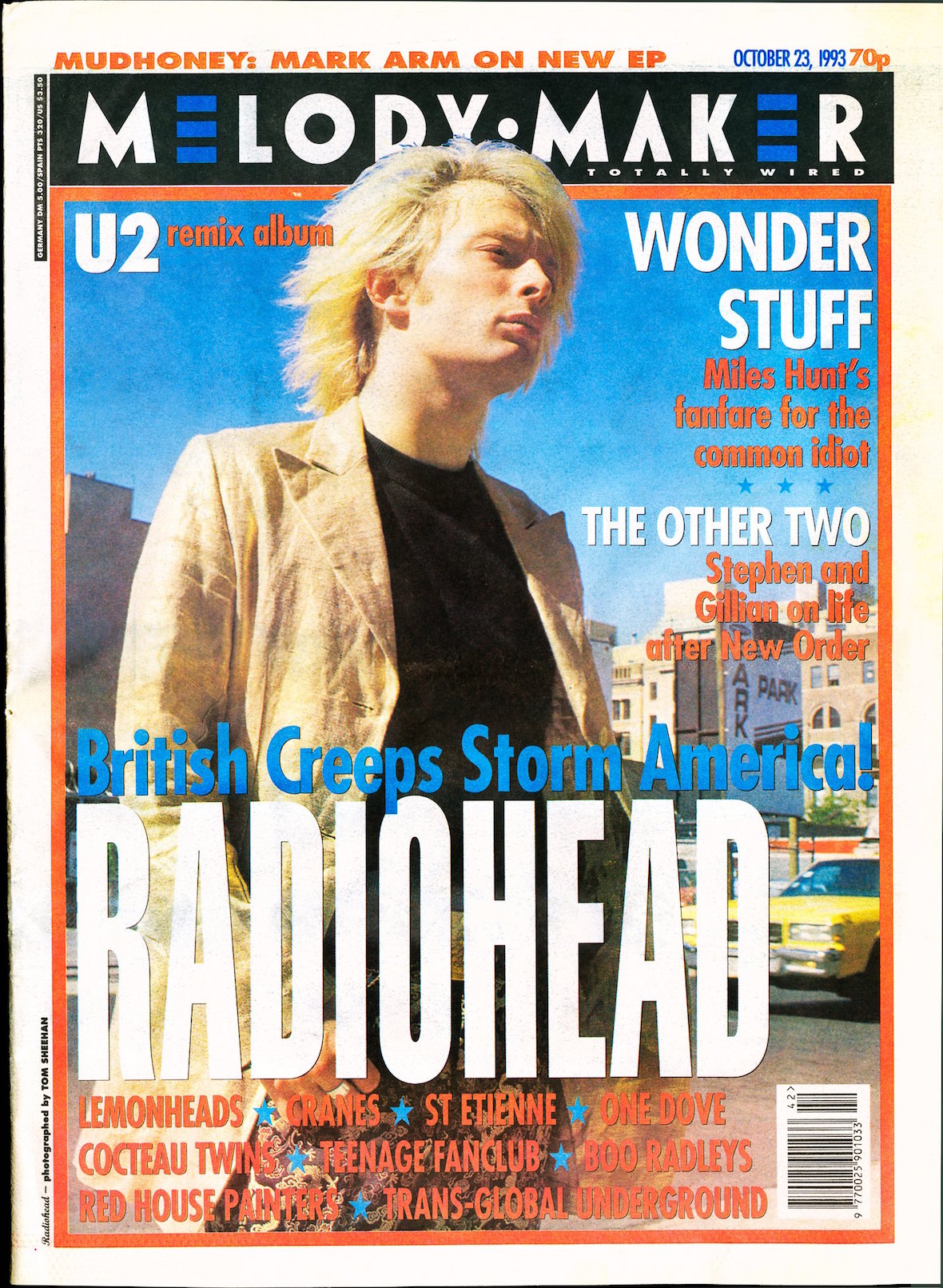

Only another 4 hours to wait until Radiohead walk onto the stage.